Chapter IX: Poetry & Flash Fiction

In Which Heidi Kasa Talks Art School, Motherhood and How To Create During the Horrors

Things are getting a little hectic this month!

I finished up a fantastic photo shoot for my author headshots at the Austin Public Library.

I’m lucky enough to be attending not one but two Austin writing conferences this month: ArmadilloCon and SCBWI’s mini MFA Conference.

And if you haven’t heard yet, my book launch is set, and you can preorder your signed copy of Hameln here.

Needless to say, talking with Heidi Kasa, an amazing poet, writer and editor here in Austin, was exactly the break I needed. I hope you’re able to sit down, cozy up and enjoy this conversation as much as I did.

I’ve edited our conversation below for clarity and length, but not cursing.

Nancy: For your MFA, you were an art school kid, right?

Heidi: I went to California College of the Arts because I wanted to go somewhere where it wouldn't be as academic, which was great because then I was with a bunch of painters and sculptors and other artists. And that was amazing, because they treat your writing as an art, right? I could have gone to get an MA, but I didn't want that academic focus.

So I think it was really good for my writing itself, but it also broke it a lot, because a lot of the teachers didn’t understand my writing. I come from a speculative sort of weirdness type, you know. And people have called it many different things, like idea-based.

But there were some people who were coming straight from just literary. I had a teacher who told me, “I don't know how to help you, because this is so far from what I think fiction is, you know?”

Nancy: [Grimaces]

Heidi: I love your face on that one, because yes, that was crushing. That was soul-crushing for a while. But at the same time, it was really a gift because I was like, "You're right, not everybody reads the same thing. And not everybody can help.” Some teachers are not good in certain areas. I appreciate that she was more upfront about it.

I think in some ways, the breaking of my writing can feel hard, but then there was a lot of growth in that two-year time period.

Nancy: It's interesting to hear you had an experience where someone told you that you were doing it wrong, and that you just worked through it instead of being like, “OK, I'm going to stop now. I'll guess I'm bad at this.”

Heidi: I think when I first heard it, I was thinking, “Oh, this must mean I'm bad at this.” And then I read more of her work, and I was like, “Oh, I see. Yeah. I also would never want to write like her, actually. I don't think this is a good match.”

Nancy: But I think that that power dynamic is hard to navigate.

Heidi: It is. It so is in an academic environment, because I'm 21. And I'm hearing from this person who is winning awards and doing really well, and they're telling me that they can't even talk about my work.

Nancy: You write flash fiction, which I want to talk about because I know nothing about it. And you also write poetry. How do you approach them differently?

Heidi: For me, it just starts with a word count. And most of it is because I'm working towards deadlines, usually. That's how I get stuff done. Is the submission call under 1,000 words? There's a little bit of a variance, but around 1,000 is what I'm aiming for.

But it's more like I have these ideas that I want to play with, and I just feel like, “Oh, this would be a cool flash thing to explore.” I think if I narrowed that down onto one scene or even a couple of scenes that I'm playing with, then that can be expanded larger in terms of the character.

I had a professor in my grad school who said “Your work is very idea-based,” and no one else I've talked to understands what that is. But the teacher who talked to me about idea-based work said, “It's like Raymond Carver's A Small, Good Thing.”

Do you know that story?

Nancy: I do not.

Heidi: Well, if I can remember correctly—it has been a little while since I read it—there's a death of a child. And then he's following the parents just after. You see them when they've just heard the news, this is so new to them, the very beginning stages of their grief and shock. And then at one point they go into this bakery, and they eat this bread, and it’s about how a small, good thing can help.

But it doesn't have a whole lot of their lives. It doesn't have a whole lot of that child, but it has that kind of idea that it's really trying to communicate.

My poetry is very image-heavy or image-rich. It usually centers around one thing that I see or smell or want to dive into. And so it's even smaller.

Nancy: I think some at some point, it was probably third or fourth grade, we learned the difference between connotation and denotation. Up until then, you're learning what a word means, and then they explain how words have technical meanings, but then there are meanings that are associated with the word. For instance, “a cabin in the woods” versus “a house in the forest;” those are very different images in your mind, you know? And so for me, poetry felt very loaded, because I have connotations for words and I recognize that my connotations for them might not be the same as someone else's. To think that the message I'm trying to relate to someone is lost simply because they have a different connotation for a word than I would: It's a nonstarter for me.

Heidi: I was just thinking about this because yesterday I was writing a poem, and revising it, and a lot changes when you change one word, right? So, I was playing around with it, and changing one word and being like, “Wow, okay, now it works.” I can see why that might be very intimidating, because there's more areas for people to lose meaning, or to not connect.

Nancy: Or to add meaning that you didn't expect.

Heidi: Yes, for sure. But I think that's really cool, to be honest with you. Because I think that it's working on those other levels, where people can hear something, and they can take away something very different than maybe you intended. To me, that's an amazing possibility, actually.

I have been misunderstood for a lot of things for a lot of reasons, so I'm not afraid of that anymore, I guess. I think our job is to just to put in the work and then have it be satisfactory to us and to our publisher and our editor. You know, we've gotten enough feedback from people we care about, and we know, and we love. Everyone else can kind of fuck off. Right?

Nancy: I love that. Let’s talk about your philosophy about creative communities. You were not the first Austin writer that I met, but you were one of the most welcoming. You have a lot of empathy; you create a lot of space for other people. And I'm wondering how you prioritize, because you have a lot going on. You're writing, you're working, you have a family.

Heidi: I think it's also like an evolving work in progress, but I do feel like I fail a lot. I have this more speculative, creative community in San Francisco that I know, but I'm not there right now. So there's a lot of FOMO, there's a lot of events that I see that I'm like, "Man, I would like to go to that!” But at the same time, some of them I'm able to support from afar.

I also feel, for me, a guiding principle is, how do we pour into each other? If I have a person who is really not also pouring into community and me in some other ways, then it's a no-go. Because they're just trying to feed off it, and they're not trying to give anything. I like to support people who I see feeding other people, trying to support other people, even if they're not supporting me directly.

Nancy: Your short story in Mixed Bag of Tricks was basically a stance on motherhood, and what it means, and how it affects people. It feels like you're writing about what can be considered very heavy, and at times controversial topics, like guns in society. What is it about those topics that inspires you to write about them?

Heidi: I don't know exactly. I don't know if it's empathy related, or if I'm just a heretic.

I am willing to say the shit that people don't want to say, and that people don't want to hear. It's so interesting that you bring up the motherhood piece, because I got so many different reactions to that. And my empathy for what people have created, the very heart of it is because my work does cause very polarized reactions.

I had a lot of mothers who cried, and were like, “Thank you for writing this, this was a gift to my heart. This was very important to me.” And then I had some people who were like, “That made me uncomfortable. I didn't like it.” I think motherhood is a tough one, because I didn't start out trying to say, “Oh, I want to put a dagger to motherhood,” you know?

Nancy: I do feel like it is a hallmark of art when you get reactions that vary that much. No one argues about a rainbow, right? It's just kind of beautiful, and it exists. It's a universally, subjectively pleasant experience. Whereas motherhood is not, and sometimes people feel that their identities are so wrapped up in it, if you attack an aspect of it, it feels like an attack on them, right?

Heidi: And I think just my very existence about motherhood can be problematic to a lot of people. And then me writing about it is just an extension of my existence of it, so they probably wouldn't have liked me anyway.

It’s funny, when you said no one argues over rainbows, because I usually can define who's gonna be my mom friend based on: Are you a sunshine-rainbows kind of mom? Or are you the one who was like, “Sometimes it's hard, let's talk about it. But also sometimes it's beautiful and amazing.” It's more complex. And I go towards the more complex.

In terms of writing about gun violence and things like that, it sort of came from more personal reactions to my world here. I moved to Texas only a few years ago, and my experience here has been so different. I guess I've lived in other states that did also have guns. But I didn't have kids then, either. So maybe that's the thing. I wasn't in an active shooter incident until moving here. I didn't see people pointing guns up trees, until I moved here. It's just so much more embedded in the culture and the lives here, and the laws. And then having my kids go to school right after Uvalde ... So I wrote it because I needed to.

But I wasn't aiming to write a collection about this. I was thinking of making a chapbook, because, well, people wouldn't want to read more than 30 pages of this, you know? That would be too hard, too heavy, too much.

And then when I put them all together, there was more interest from a publisher. I really started to think about how this isn't just anti-gun, and this isn't just my personal experiences with it. I'm starting to explore some of the other aspects of it, too. It's bigger than that.

Nancy: I can't wait to read it. I'm very excited. I'm—“excited” is the wrong word. I'm very intrigued. I remember Sandy Hook hit differently for me because they were so young, and I was a new parent. And we've talked about how I had a colleague killed in a shooting in a newsroom, because that's another thing that’s started happening more often—reporters being attacked and being targeted just for being journalists. I remember talking to you about that and tearing up a little because I'm a weepy little crybaby sometimes. And I really appreciated how empathetic you were about it, and how careful you were with the stories I was telling you. In The Bullet Takes Forever, I know a lot of it is personal to you, but were you using other people's experiences?

Heidi: It was a lot of what I heard at the time, too, from various people. And I mean, I'm not going to call anyone out here.

Well, actually, no, I can call my husband out.

I think it was Uvalde, and my daughter was supposed to go to kindergarten after that happened. And he goes, “Should we homeschool?” And then, because of that, I wrote this poem called "Don't Say Gun,” which lists what I say to the father who wants to homeschool their child: the churches, malls, all the places where [gun violence] has happened that I know of. Because the thing is, when I was researching it, there were so many more than I even knew about. There was one in Texas in 2023, like a pretty major one that I didn't even know about. And I fucking live here. You know what I mean?

What I heard about Uvalde was, “Yeah, the worst part about that one was the cops not going in.” And I'm like, “Is that the worst part of that?” 'Cause I think the worst part about that one for me is so many things: the 19-year-old got a gun, when he wouldn't have been able to just a year before. And obviously the worst part is the kids and their deaths. And then you go through all these other layers of trauma, and all these people who watch on the news, and it's too much in our consciousness, right?

I'm not trying to take away people's guns. I don't think that we should, and it's never going to be possible anyway, to be gun-free. Especially in America. But for me, it's having more control of it, and more laws that actually do serve our current reality.

Nancy: What do you do to keep yourself going during this daily life and the traumas? What does your writing routine look like?

Heidi: As a mother of young kids, I think that's why I had to veer into flash fiction and poetry, because those are things that I can dip into during the day when I get a chance.

Nancy: Especially since you're so idea-driven, is it experiential or is it literally just coming out of your head?

Heidi: I think that's one of the things I struggle with, having young kids, is that they do suck time from your head. You're having a thought, and your kids are like, “I want juice.” And “Can you watch me do this?” And all of a sudden, you're writing “juice” instead of whatever the word was. And I'm going insane because I can't even finish a thought in my head. That's one of the things that was in my mother story for sure, is the drain on my energy and thought process. But I do think that when they're at school, I delve into things more often, and that's really helpful.

And if I have an idea, I write it down, even if it's just an impression of this tree that I saw. Even if I don’t know where this is going to go yet.

I was traveling recently, and I saw this door that someone had in their lawn. Just a door, leading to nowhere. So I took a picture and I started to write a poem about it: the door leading to everywhere or nowhere, you know? It seems like it'll probably be a poem, but then who knows? Maybe that will be something else that will spark some idea, some story. I mean, I don't even know.

Nancy: I really enjoy your Instagram because of those types of images, and I love your captions. It's always a completely different perspective, and I really enjoy getting a peek into your head like that. I think that's why we all read, right? To get a peek into someone else's head.

Heidi’s One More Thing

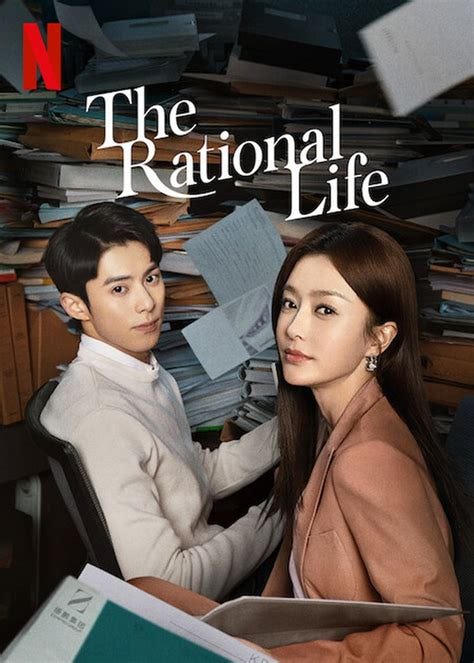

“I find Korean rom-coms great for blending with other genres. You'll be watching a silly, sappy rom-com, then halfway through there's suddenly some gore and other horror elements. Or you'll think it's a rom-com until the end of the second episode when shit gets real and you're in a political thriller with espionage, but still a love story track you're following. Just a bumpier ride. I found a Chinese rom-com called The Rational Life on Netflix. I adore the main character. She doesn't kowtow to people's bad or bullying behavior—she's strong and self-aware. She inspires me to meet challenges head on with a composed manner.”

Heidi Kasa is the author of the poetry collection The Bullet Takes Forever (Mouthfeel Press, 2025), the flash fiction collection The Beginners, winner of the 2023 Digging Press Chapbook Contest (2025), and the fiction chapbook Split (Monday Night Press, 2022). Her writing won the 2024 Plaza Prose Poetry Prize and the 2023 Poetry Super Highway Contest, and was chosen as a finalist for Best of the Net, Fractured Lit, Black Lawrence Press, and ESWA Crossroads contests. Her work has appeared in Barrelhouse, The Brooklyn Rail, and The Pinch Journal Online, among others. She works as an editor and creates handmade artist books. Find her at www.heidikasa.com.

Beautiful interview! So many relatable elements and new perspectives. :)

Thank you so much for featuring me and for this conversation, Nancy!